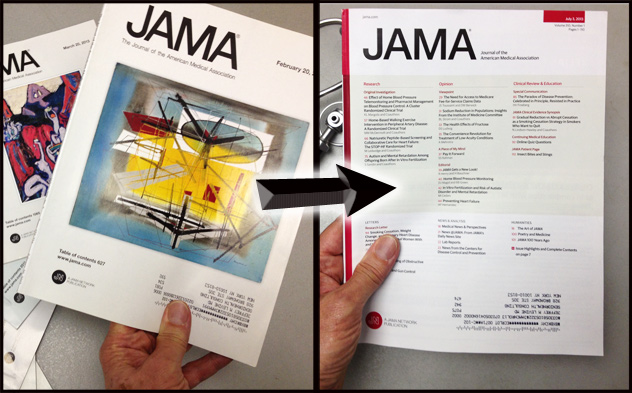

Beginning in 1964 the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) started publishing full color images of art on its cover accompanied by insightful essays. JAMA’s former editor, George Lundberg, wrote that this was part of an initiative to inform readers about nonclinical aspects of medicine and public health, and emphasize the humanities in medicine. Now after almost 50 years of covers that displayed over 2,000 pieces of art, JAMA has taken a great leap backwards and replaced the cover art with a pedestrian table of contents. The cover art that once distinguished JAMA from an array of leading medical journals has been demoted to an inside page, eliminating one of the more visible, inspiring beacons that once linked the humanities to medical science.

The cover art was always important to me. As a teenager envisioning my future, I saw copies of JAMA on my uncle’s desk. He was a medical doctor, and for me the JAMA covers joined the visual arts to the science of medicine and gave me inspiration. As the years passed, I enjoyed seeing the distinguished covers of JAMA in medical libraries, and frequently picked them up to read the commentary. Glancing from the scientific articles to the essays on the cover art, my vision of the combination of art and medicine was validated. Over the years I received JAMA in my office and tacked many of my favorite covers to the wall by my desk.

The art swept across the vast panorama of civilization and human history. Just about any painter you can imagine has been featured on a JAMA cover. In addition the covers displayed Japanese Ukiyo-E prints (February 4, 1998), a 15th Century Apothecary Treatise (September 8, 1999), and African bronze statuary (April 6, 2011). One of my favorites was the photo of the Lewis Chessmen, a set that was carved from walrus ivory in the 12th Century and found in the Outer Hebrides off the coast of Scotland (February 16, 2011).

Some covers provided provocative visual imagery that accompanied an issue’s contents and reflected concern with public health and social issues. For example, in February 28, 1986 Van Gogh’s Skull with Cigarette was featured on an issue that compiled several articles on smoking. In November 13, 2002 a special issue on aging was graced by a painting by Minnie Evans, an artist who began to draw at age 43, then drew for another five decades. One of the most affecting covers was July 1, 1998 on an issue that presented the latest HIV/AIDS research. This cover was blank, and entitled A Cover Without Art. As written by the accompanying essay by M. Therese Southgate, “It is the blank canvas that reminds us of how much there is yet to do.”

The cover art made JAMA a beacon for humanism that shouted out its presence in a sea of technological advancement, and reminded us that medicine is closely intertwined with people and culture. In marketing terms, the revised cover represents rebranding not only of JAMA but perhaps of the medical profession itself. The change comes at a time when medicine sorely needs a touch of humanism, and rather than taking art away we need more of it.

But perhaps this cover redesign is symptomatic of a deeper culture change in the medical profession. Medicine is no longer in the realm of the private practitioner working as an independent problem solver, but instead has become a data driven, technology oriented business, and in a team environment the physician’s status has been demoted to “provider.” It is no wonder that the artist – representing an individual defining him/herself alone in a studio with brushes and paints – is no longer an appropriate symbol for the cover of a prestigious medical journal.

For over 30 years at JAMA, M. Therese Southgate served as Cover Editor, choosing them and writing incisive commentary on the work. These covers along with the essays were collected into books that you can find on Amazon. In an inspiring essay on her philosophy on art and medicine she wrote:

“Medicine is itself an art. It is an art of doing, and if that is so, it must employ the finest tools available — not just the finest in science and technology, but the finest in the knowledge, skills, and character of the physician. Truly, medicine, like art, is a calling.

And so I return to the question I asked at the beginning. What has medicine to do with art?

I answer: Everything.”

In an editorial in the first newly redesigned issue dated July 3, 2013, the editor writes: “The goals of the redesign were to create an inviting, visually lively publication…” but the result does not fulfill this intention. There is more than a cosmetic issue at stake. JAMA covers have been the face of this medical journal for almost 50 years, endowing the profession with the face of humanism and social concern that it sorely needs. In an attempt to adapt to the future, lets not go back to the past.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

jz4vu3

A fantastic article! I am an ER physician and an artist and belong to both worlds. The loss of JAMA art is such a disappointment. I hope they reverse their decision at some point, it was such a distinguishing feature of JAMA.

It’s never too late to fix a mistake.

I was introduced to these wonderful covers and Therese Southgate’s excellent essays in my physician’s office. She has a copy of the first volume of the Covers and Essays from JAMA. I finally decided to order my own copy and was delighted to discover that two later volumes are available. I ordered those as well.

Wonderful artists continue to create provocative, original work. JAMA could have hired an equally insightful, compassionate, freelance art historian to continue this tradition. How sad for the rest of us they did not.

It baffles me that the editors thought that putting the table of contents, an informative, but positively dreary visual invitation, would be better.

Thank you, M. Therese Southgate, MD, for publishing these the magnificent collections. They are the jewels of my modest art library.

Kathryn Tidyman

Retired for 2 years, I became aware of the loss of the cover art on JAMA when I received a plaintive note from my (only) daughter telling me it was no longer there. We are not artists, or even very knowledgeable about great art. Theresa Southgate’s discussions frequently were way beyond me. But often I saw something on the cover of JAMA I liked and shared it with my daughter in her younger years to expose her a bit to the “arts”–With math, science, and languages, there was never time for an art course. My daughter evidently enjoyed this low key exposure and is now attempting the same thing with her daughter. Alas, no more JAMA cover art! What a loss!

Many a week in the past 45 years it was one of the best parts of the Journal! Perhaps we will have to get the books of past covers and start picking a painting every week or so to discuss. Not quite as spontaneous or low key as weekly covers, but all that we have. Isn’t it wonderful when one finds where we successfully “reached” our children? And the supreme compliment: wanting to re-use the same technique with their children! All of that, from a medical journal!

Well, your essay on the loss of JAMA covers reflects my sad thoughts. Over the years I have collected many covers, had them signed by the artist and now those images grace our hallway (they are so light-sensitive), framed by me. Ha, Roy Lichtenstein, a couple of Jacob Lawrence’s, Frank Stella, Jamie Wyeth, a few David Hockney’s, on and on, all in my own private museum! I have not heard of a similar collection, even Dr.Southgate knows of none. With one of the artists a serene friendship evolved. She even painted a picture when our grandson Max May was born 21 years ago, one of his treasures. A few years ago I put together a talk The Art on JAMA. I first presented this slide show of my gems at one of the meetings of the American Osler Society (of which I am a member).

So, thank you much for your insightful essay, best wishes, Claus

I’m not a subscriber–I read someone else’s issues and then pass them along to another reader. I don’t like this at all, for all the reasons you give (excellent), plus if they stack up on the couch, I can’t identify at a glance what I was reading. But glad I found your blog.

Rachel Baker has sent me your comments about the cover page of JAMA. Your views coincide with mine. I was sorry to see the beautiful images and paintings removed from the cover page and hidden among the advertisements where nobody will look at them. After all, a little culture would not harm our practicing physicians, bombarded weekly as they are with articles on guidelines, suggestions for curriculum changes, reimbursement issues, and studies whose outcome even New York taxi drivers could predict. There was indeed a time when most journals had their table of contents on the front page. This is very convenient and saves space, but does not need to be done in a gray unattractive format.

Please keep on writing and using the right side of your brain.

George Dunea MD, FACP, FRCP (Lond & Edin), FASN.

Editor in chief, Hektoen International

Late to the “party”, but wanted to express my wholehearted agreement with your article. I am deeply saddened that the artful cover is gone. I have one of the books and have cherished the covers and articles for years. While not an MD, I am managing editor of a medical journal and struggle with cover art and identification all the time. JAMA was what I wish we could do, now it looks like everybody else.

I do not like the removal of cover art. I think it was the best part of the Journal.

My wife has taken covers to school to share with students.

Thanks for expressing what I have been thinking and feeling. I’m glad to know that others are mourning this “loss” for to me that’s what it is. When I saw the first new cover, I felt like I had lost an old friend. And I have.

JAMA has joined the AMA which has joined the public’s (erroneous) ideology that health can be bought. An ideology run by MBAs rather than MDs.

Miss old JAMA.

I thought of you immediately when i saw the ‘new JAMA’, and was hoping to talk with you about it. I felt an immediate sense of loss and emptiness, coupled with a feeling of vulgarity. It was as if, absent the art, the journal, The AMA and our profession had exposed its ugly naked self. With out getting too carried away, the new cover seemed like a perversion to me. Perhaps the new cover is more honest, in which case I would say, I will take dreams over reality any day.

So the AMA has finally dropped the pretense. The medical profession has not for a long time seriously attempted to integrate so-called art of medicine with so-called science of medicine. At least now the cover more honestly reflects the mindset of those that lead the profession.. Like you, I am profoundly saddened by this change and I recognize that this is just a symptom of a profession that has its priorities seriously confused.

Thanks for sharing your commentary. I wholeheartedly agree.

I’d add, though, where you describe medicine as increasingly “data-driven,” that medicine is increasingly driven by a specific type of quantifiable, statistically analyzable data — rather than remaining appropriately informed by the various kinds of data that in fact underlie human health, care, and treatment. (This difference is, in my mind, where medicine has everything to do with art.)

I’ve been following the plight of humanities programs at universities, which I think connects to the change in the JAMA cover. As you no doubt are aware, fewer students are taking courses in the humanities and/or majoring in those fields. The students assume that they cannot get a good job with such majors. My guess is that the cover change reflects the lack of respect that people interested in humanistic studies are receiving.

You are unusual because you take photography seriously as well as medicine. I’m glad that you brought this change to our attention and hope that somehow we can resist the diminishing of respect for humanities scholars and those who combine their scientific and humanities interests.

Great commentary. I am not a subscriber so thanks for making me aware if the change. When I was enjoying my institutional subscription the cover art tapped an undiscovered interest in art. I clipped out the graphics kept them displayed and rotated on my bulletin boards. I learned from the essays.

It’s a loss. A sign of the cost cutting period we are in and likely will be for the long hall. Everything mission driven and all unessentials stripped away. The arts are expendable. My NYC public school music teacher husband’s experience has made this clear. Parents have been fighting cuts and winning but it’s always a battle.

In reviewing the journal change I feel better that the art is preserved inside for the JAMA reader. The editors surveyed readers and a senior colleague at JAMA said, “Art is not JAMA.” Let’s hope that the humanities pieces currently integrated aren’t discarded in the future.

The beauty of the JAMA cover is gone sacrificed for the digital platform and so it goes. It sure was a standout on library shelves. Now it’s just another black and white nondescript journal. Beauty sacrificed for function.

For decades the covers have distinguished JAMA from all the other look-alikes. This is yet another example of “the art of medicine” being diminished — this time literally! It represents a kind of homogenization which saps originality and vitality out of the profession. Very sad.

How sad that the actions of JAMA, noted in this superb article, creates the opposite of medical treatment’s purpose:

It makes me sick!

Jeff, read it, agree, good for you. 2 thoughts:

Yes, it is symptomatic but I would say of a different illness: it is an anomie on the part of current medical journal editors for medical humanities, as represented by their emasculated descriptions of what is acceptable any more for same (read politically correct proscriptions) and the etiolated stuff they do publish. The New England Journal limiting their med humanities-type column to 5 references???? Please!

As someone who had Terry Southgate to UConn for an art med conference, I can tell you that they are deleting their copy to spite their own face and know it: they protesteth too much. That art-cover tradition was a wonderful JAMA contribution to medical journals and JAMA violated the first rule of medicine: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Jeff, what a fabulous article! Good for you for recognizing so astutely the great symbolism involved in this disappointing decision by JAMA editors. As you write so eloquently, this is not about cosmetics – or even functionality. It speaks to the heart and soul of medicine. As is so often the case, a picture is worth a thousand words, and the two covers at the start of your essay say it all. Finally, thanks for the history lesson on past JAMA covers. I remember the HIV/AIDS cover well – heartbreaking. Great work, but how sad it had to be written. Johanna Shapiro

Now as “inviting, visually lively” as a morgue.