I’ve spent a lot of time studying physicians who were also successful artists, poets, and writers. Examining their work and lives, I try to decipher how they succeeded in two challenging careers during the same lifetime. With this in mind, on a trip to Moscow to photograph aging I made a point of visiting Dr. Anton Pavlovich Chekhov. Born in 1860 in a small town in Ukraine, Chekhov entered medical school at Moscow University at the age of 19. He made extra money to support his medical studies selling short stories, although at first he was not serious about becoming a writer. At age 24, the year he graduated, he coughed up blood and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. In those days this disease was incurable and as a young physician he must have known it would eventually kill him. I wonder if knowledge of his impending death gave him purpose and urgency to develop his creativity.

Born in 1860 in a small town in Ukraine, Chekhov entered medical school at Moscow University at the age of 19. He made extra money to support his medical studies selling short stories, although at first he was not serious about becoming a writer. At age 24, the year he graduated, he coughed up blood and was diagnosed with tuberculosis. In those days this disease was incurable and as a young physician he must have known it would eventually kill him. I wonder if knowledge of his impending death gave him purpose and urgency to develop his creativity.

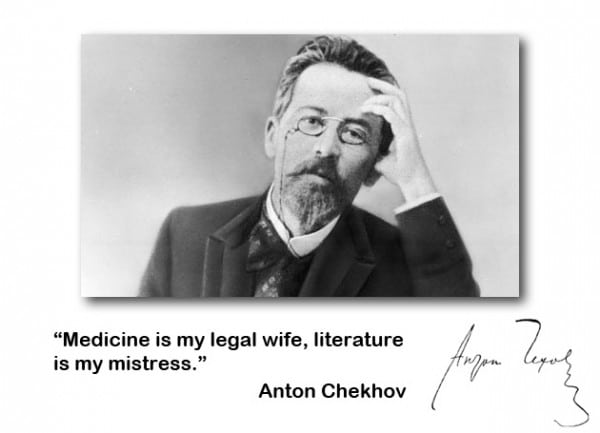

Chekhov lived another twenty years – a long time for someone with pulmonary TB in the pre-antibiotic era. He practiced medicine most of that time while developing his talent as a writer. He described the relationship of his two callings:

“Medicine is my legal wife, literature is my mistress. When I’m bored with one I spend the night with the other. This is irregular, but at least not monotonous, and neither suffers from my infidelity. If I did not practice medicine, I could not devote my freedom of mind and my stray thoughts to literature.”

Chekhov had an eye for human idiosyncrasy and a knack for depicting human pathos in the lowest strata of society. Doctors feature prominently in his work, and I enjoy the way he humanizes them. One example is in his masterpiece short story, Ward Number 6, where he provides a penetrating psychological study of a doctor named Andrey Yefimitch. Years ahead of his time, Chekhov describes the transformation of a physician burning out from too much work:

“At first Andrey Yefimitch worked very zealously. He saw patients every day from morning till dinnertime, performed operations, and even attended confinements. The ladies said of him that he was attentive and clever at diagnosing diseases, especially those of women and children. But in process of time the work unmistakably wearied him by its monotony and obvious uselessness. Today one sees thirty patients, and tomorrow they have increased to thirty-five, the next day forty, and son on from day to day, from year to year, while the mortality in the town did not decrease and the patients did not leave off coming. To be any real help to forty patients between morning and dinner was not physically possible, so it could but lead to deception. If twelve thousand patients were seen in a year it meant, if one looked at it simply, that twelve thousand men were deceived.”

At the time he died at age 44, Chekhov was a major literary figure in Russia. He had given up medicine as a primary career but still provided medical care to poor peasants for free.

Chekhov was buried in the Novodevichy Monastery, founded in 1524 on the outskirts of Moscow – a coveted burial place for Russian nobility and war heroes. His remains were moved to the adjacent cemetery where he rests today under an austere white monument seen in the slideshow above. He is surrounded by great Russian scientists, philosophers, astronauts, and famed artists and writers such as Nicolai Gogol, the film-maker Sergei Eisenstein, the cellist Rostropovich, and composers Sergei Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich.

A strange thing happened to me when I went to visit Dr. Chekhov. As I walked through the gates of the Novodevichy Cemetery the heavens opened up and without an umbrella I became drenched with rain. The rain continued until I left the cemetery, when the skies magically cleared.

Anyone who has read Chekhov’s short stories knows that many take place against a backdrop of bad weather. Indeed, one of his stories is even entitled Bad Weather. In retrospect, maybe this was Chekhov’s playful way to greet me when I came to visit him. In searching for the root of Anton Chekhov’s gifts, he gifted me with raindrops and memories of a lovely afternoon in Moscow.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The Chekhov quote regarding literature and medicine is from Doctor Chekhov: A Study in Literature and Medicine by John Coope, published by Cross Publishing, Chale, Isle of Wight, 1997.

Related posts:

The Ticket That Got Me Through Medical School

An Abandoned Psychiatric Hospital in Tuscany

Goya’s Physician and the Art of Caring

Wounds of a Boxer: Medical Secrets from Ancient Rome

JAMA is Redesigned, Art is Demoted

.

Hey Doc,

I just finished reading Ward 6 last night with much delight. Your insight is accurate that Dr. Chekhov is ahead of his time, and his influence and humor reminded me of the work of Woody Allen.

Thanks for sharing.

Mike

Your insights and narrative reflect your own ability to juggle several careers and share your talents/gifts that are inspiring and appreciated.