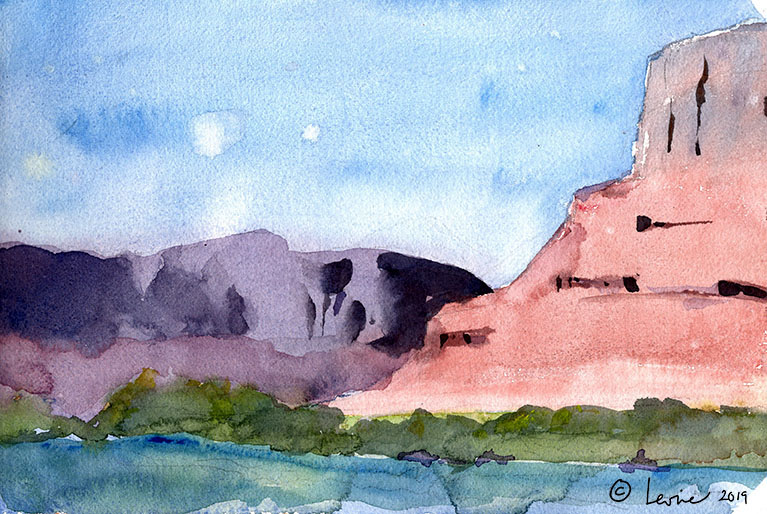

In the heat of the southwest desert, among the towering buttes and mesas of Red Rock country, I discovered the thrill of watching paint dry. I’ve been doing watercolor for years and found the most difficult part is waiting for each wash to dry before proceeding to the next. In Utah, the combination of sunshine, dry winds, and low humidity caused paint to dry so quickly you could watch it.

Watercolor painting usually strives for the glowing effect from transparency of the pigments. This is produced by physics, when light is reflected from the white paper through a layer of paint. The effect is destroyed if opaque pigments are used, or if the law of layering is violated. This law requires each layer to be “bone dry” prior to applying the next one.

If done correctly the effect is magical. Watercolor masters of the past like Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent were well aware of this and skillfully employed it to make their paintings glow. The technique is used by contemporary masters like Frank Webb and Shari Blaukopf with wonderful luminescent effect. But the key to successful layering is waiting for paint to dry.

When first learning watercolor, in my impatience I tried layering on damp layers. That works fine if you intend to work wet-in-wet, but when building up transparent layers the effect is dreadful. The freshness of a wash is destroyed and what is left looks like dried mud. Thus the importance of waiting for paint to dry.

Many watercolorists use an electric hair dryer to accelerate the process, but purists claim this makes washes look flat and dull. When painting outdoors, hair dryers are out of the question and the artist is dependent upon ambient temperature and humidity, both of which impact drying time. I remember a cold foggy day in Maine when my paper was still damp hours later.

There are two sources of moisture on wet watercolor paper. One is water pooled at the surface that you can observe by holding the paper at an angle and seeing the sparkly reflections. The other is water molecules within the paper fibers that are held by capillary action, that you can feel with the back of your hand.

Drying requires energy to transform water from liquid to vapor, and an air stream to remove the vapor. High humidity will retard drying due to a phenomenon known as vapor pressure. When paper dries it absorbs energy, thus the cold sensation when touched. When temperature is low, humidity is high, and ventilation is minimal, wet paper will be very slow to dry.

So let’s get back to watercolor in the Utah desert. The sun was bright and warm, humidity non-existent, and a brisk breeze blew through the canyons making ideal conditions for fast drying washes. I was actually able to watch the surface liquid recede and the paper turn bone dry within seconds after a wash, enabling quick progression to the next layer.

When someone mentions watching paint dry they’re usually referring to an extremely boring activity. For a watercolorist in the desert, this is definitely not the case. Painting in southern Utah in the Red Rock canyons I discovered that watching paint dry can actually be an amazing thrill.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Sketching the Subway and the Disappearance of Time

Plein Air Painting in the Hudson Valley

Plein Air Painting on the McKenzie River

The Corpus Callosum, Buddha’s Enlightenment, and the Neurologic Basis for Creativity

Thanks for the comment Janet. Thats a great solution provided you have the extra space not to mention the extra paint!

Very nice explanation. Your explanation of the mud effect so aptly describes my early problems with watercolor. I try to get around my impatience by having several versions going at the same time. This is much harder to do outdoors.