Over the past month an ancient sculptural masterpiece has been on temporary display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Greek and Roman halls. On loan from Rome’s Museo Nazionale Romano, “Boxer at Rest” depicts a battered pugilist immediately after a fight. His face bears evidence of broken nasal bones, swelling and hematoma under his right eye, and multiple lacerations and abrasions to his nose, cheeks, and forehead. One secret I have not found mentioned in literature on this striking life size sculpture is evidence of medical treatment for hematomas of his ears.

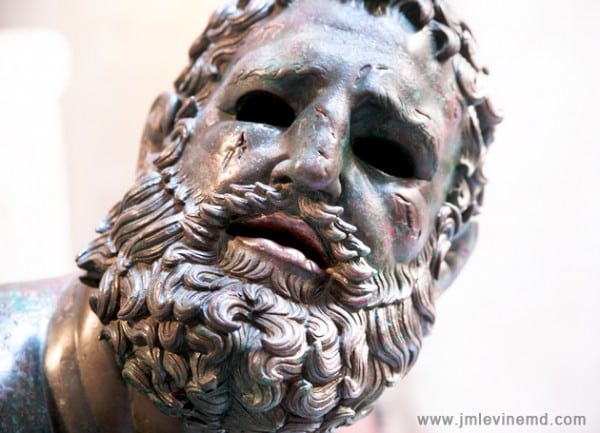

Face of the Boxer showing fresh bruises and lacerations

The sculpture is made of bronze, and scholars date its completion between 350 B.C. and 50 B.C. It once stood in the Baths of Constantine – a bathing complex and cultural center in ancient Rome. His only clothing is a pair of elaborate boxing gloves and a leather strap on his foreskin to conceal his penis (kynodesme). Boxing was a revered sport in the ancient world, and there were few rules to the game. This statue may have had magical powers evidenced by areas of wear on the hands and feet caused by frequent rubbing over decades, perhaps in hopes of victory in the arena or healing from an injury.

The Boxer’s ears have fresh incisions that are bleeding.

The Boxer has evidence of multiple injuries that are skillfully rendered and anatomically correct. There is acute swelling from hematoma under his right eye that is indicated by an inlay of darker metal. But the ears exhibit not just swelling that could be both acute and chronic from prior fights, they also display clean wounds that may have been administered by an iatrós – the old Greek word for physician. There are inlays of copper alloy that emphasize these incisions and the blood dripping from his ears and onto his thighs.

Lool closely and you can see fresh blood dripping onto the Boxer’s thigh

Hippocrates lived on the Island of Cos between 460 and 370 BC, and his writing laid the foundations of medical treatment for generations of physicians. At the time this statue was cast, his principles were well known in the ancient world. At first glance, the ears look simply swollen and bleeding with what is commonly described as “cauliflower ear.” But if you look more closely there is evidence of freshly performed surgical treatment of hematomas sustained in the pugilist’s match. In Hippocrates’ work entitled “On Injuries of the Head,” he specifically prescribes incisions for healing:

“Incisions may be practiced with impunity on other parts of the head, with the exception of the temple and the parts above it, where there is a vein that runs across the temple, in which region an incision is not to be made.”

Other treatments of the day would include washing the incision with wine and stopping the bleeding with juice from a fig tree.

O bservations on details of the Boxer’s wounds support my theory. There are three incisions on his ears, two on the right and one on the left. Each incision is neat, horizontal, and dripping fresh blood. This is emphasized by the sculptor, who presents these incisions and their bloody drainage with a lighter alloy of copper. In contrast, the cuts on his face, nose, and forehead are ragged and multi-directional. When these lacerations are compared to his ears, the neat horizontal incisions stand out as being administered after the fight by a skilled hand.

bservations on details of the Boxer’s wounds support my theory. There are three incisions on his ears, two on the right and one on the left. Each incision is neat, horizontal, and dripping fresh blood. This is emphasized by the sculptor, who presents these incisions and their bloody drainage with a lighter alloy of copper. In contrast, the cuts on his face, nose, and forehead are ragged and multi-directional. When these lacerations are compared to his ears, the neat horizontal incisions stand out as being administered after the fight by a skilled hand.

The Boxer’s gloves were constructed to ensure injury to his opponent

This treatment makes sense. A cauliflower ear is an acquired deformity that begins with a pocket of blood called a hematoma that develops between skin and cartilage, disrupting the perichondrium that supplies nutrients. If untreated, several complications can occur. For example the hematoma can become infected, or the cartilage can die causing fibrosis and scar tissue with permanent swelling. Then, as now, the treatment for a hematoma is sometimes incision and drainage.

So what does this messenger from the ancient world have to tell us? He is depicted sitting, exhausted and bloodied after a match. His head is turned sharply to the right and looking up, perhaps at the cheering crowd or the judges who are announcing his rank in the pugilist competition. This is what is conveyed in the museum literature, but I have an alternative explanation. Perhaps he is turning his head to show his bruises to a physician, who just made incisions in the swollen areas to drain blood and help him to heal. Fresh blood falls on his right thigh as he patiently waits for the iatrós to tend to his wounds.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

References for this post included:

Man and Wound in the Ancient World by Guido Majno, Harvard University Press, 1975.

On Injuries to the Head, by Hippocrates, translated by Francis Adams.

The Boxer: An Ancient Masterpiece Comes to the Met, by Sean Hemingway.

Related posts:

Jewish History in Vesalius’s Fabrica

The Enigma of the Historiated “V” in Vesalius’s Fabrica

Aging on the Covers of The Gerontologist

Celebrating Old Age at the Burning Ghats of Benares

Victory Day in Moscow

A Taste of Ancient Peruvian Medicine

The Twilignt of Jewish South Beach, Miami

The Elders of Taquile Island in Peru

Aging in Central Asia

Photographing Los Ancianos of Bolivia

Aging Inside Angola State Penitentiary

Faces of Istanbul

Geriatrics, Art, and Ancient Treasure on Lake Titicaca

An Abandoned Psychiatric Hospital in Tuscany

Photographing Letchworth Village

Your stunning photographs and insights will make the visit to the exhibit so much more meaningful. Thank you.

Who knew? Cauliflowers fixed Italian style. I’m surprised that you didn’t mention that Galen treated gladiators and that was the closest he got to studying human anatomy – as our friend Vesalius found out.