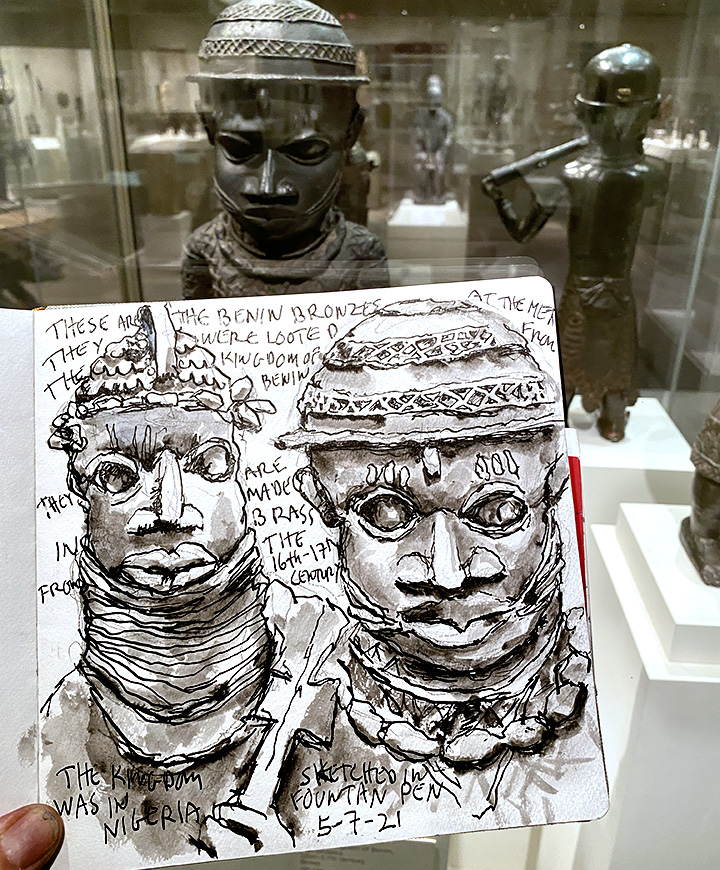

On a recent Friday as the pandemic lockdown was lifting, I spent the day sketching at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. On my list was the Benin Bronzes, spectacular sculptures which bear the stigma of colonial plunder, and have a dark and bloody history that belies the serenity of the African gallery which was mostly empty. Their deep darks and somber tones offered exceptional opportunity for fountain pen and waterbrush.

Benin was a kingdom in West Africa whose history began in the 13th Century, in what is now Nigeria. The culture was destroyed by the British in 1897, and over 3,000 items representing five centuries of art and religious objects were removed and scattered worldwide to museums and private collections. The largest holdings are in the British Museum and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, and the Metropolitan in New York City has over 150 pieces. In recent years, the movement to repatriate these splendid examples of African Heritage has accelerated.

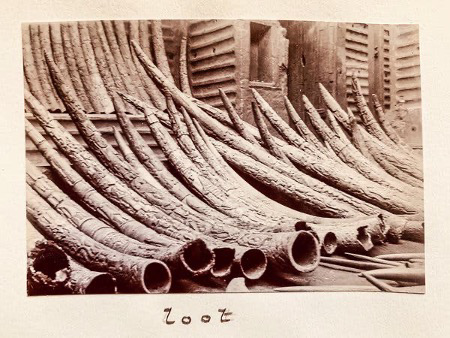

This photo shows the scale of plunder by the British who destroyed the Benin culture.

Although the works are called Benin Bronzes, they are made of various materials including brass, wood, ceramics, ivory, and leather. Prior to its destruction, Benin had a sophisticated social system, and was famous for its artistic craftsmanship. The kingdom came to a quick end as described in a book entitled Benin: The City of Blood by Commander R.H. Bacon who took part in the military action, and his text demonstrates the evil of colonialism.

The defenders of Benin were hopelessly outgunned against British armament that included explosives, cannons, rockets, and Maxims – machine guns that shoot 100 rounds in ten seconds and considered one of the deadliest weapons in history. Bacon describes destroying crops, burning royal homes, and driving residents into the bush. He says little of Benin culture while dwelling at length on the practice of slavery and human sacrifice as moral justification for destruction of Benin civilization.

The Maxim machine gun was used against the people of Benin, and later became a weapon of choice in WW1.

The racist attitude of the plunderers is reflected in the author’s narrative when, after leveling the city he writes, “… they cannot fail to see that peace and the good rule of the white man mean happiness, contentment, and security.” On their return, the regiment received congratulatory telegrams from the Queen.

It took me a few minutes to find the Benin Bronzes which were located in the center of the expansive gallery. I was surprised how many pieces there were as well as the variety of media, which included a spectacular carved elephant tusk, learning later that the Met has over 150 pieces in their collection. As noted by artist Victor Ehikhamenor in an essay in the New York Times, the masterpieces that I was sketching have never been viewed by generations of Africans who have lost both their history and cultural reference points. Standing silently while sketching in the empty gallery, it is difficult to imagine the majesty and meaning once held by these sculptures. There is no better example of the mystery and power of art, and how it reflects on both the highest and lowest ideals of humanity.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The photo of tusks was reproduced from the New York Times article entitled This Art Was Looted 123 Years Ago, Will It Ever Be Returned? The Maxim gun photo is from the online Encyclopedia Britannica.

Related posts:

Sketching Flora and Priapus at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Turner Watercolors at the Mystic Seaport Museum

Sketching at the Museo del Prado

Goya’s Physician and the Art of Caring

Wounds of a Boxer: Medical Secrets from Ancient Rome

Tradition and Healing at the Santa Fe Indian Market

Jewish History in Vesalius’s Fabrica

3zuaip

ivx3oo

5fhzwt

blhj1x

lo8opl

s0ctfd

7pq5ao

az3175

39ezpc

len6sp

6fiipe

gy679g

i1ckr7

mhr9cn

frchk4

9d34ha

sjr1j0

9j0v40

zck3i5

2oyxuz

jqd6ku

rsr5m3

s8yp6y

d2gts6

6ae63b

kljw61

ztwi6i

4nqqfn

1ncynm

k4u6w0

lpe79h

The research for this post opened my eyes to the vast problem of plundered art, and the sticky and complex issues of their return. thanks for the comment!

While it is admirable that items plundered by the various colonial powers be returned to the lands from which they were taken. However if done, then it is to be hoped that the process is done with caution and honest governance. It would be a sad situation if the items currently on public display, landed into the hands of a corrupt official or politician who kept them for their own viewing and or even worse, sold them to private collectors.